profound and significance to the development of Chinese Buddhism and Zen Buddhism.

Overview

Chinese Name: 惠能

English Name: Huineng

Other Names: Huineng 慧能

Born: 638 AD

Died: 713 AD

Achievements:

commonly known as the Sixth Patriarch or Sixth Ancestor of Chan 被誉为禅宗六祖

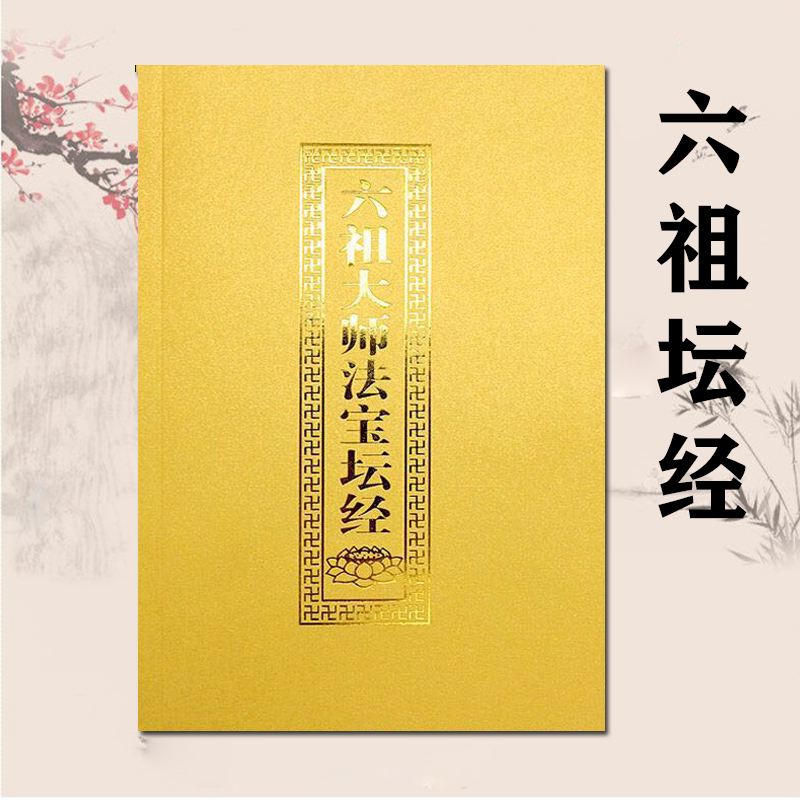

created The Platform Sutra of the Sixth Patriarch 创作了《六祖坛经》

It is of profound and solid significance to the development of Chinese Buddhism and Zen Buddhism.对中国佛教以及禅宗的弘化具有深刻和坚实的意义

Brief Biography of Huineng

The two primary sources for Huineng’s life are the preface to the Platform Sutra and the Transmission of the Lamp. Most modern scholars doubt the historicity of traditional biographies and works written about Huineng, considering his extended biography to be a legendary narrative based on a historical person of “merely regional significance,” of whom very little is known. This legendary narrative reflects historical and religious developments which took place in the century after his life and death.

According to Huineng’s autobiography in the Platform Sutra, Huineng’s father was from Fanyang, but he was banished from his government position and passed away at a young age. Huineng and his mother were left in poverty and moved to Nanhai, where Huineng sold firewood to support his family.

One day, Huineng delivered firewood to a customer’s shop, where he met a man reciting the Diamond Sutra. “On hearing the words of the scripture, my mind opened up and I understood.”

He inquired about the reason that the Diamond Sutra was chanted, and the person stated that he came from the Eastern Meditation Monastery in Huangmei District of the province of Qi, where the Fifth Patriarch of Chan lived and delivered his teachings. Huineng’s customer paid his ten silver taels and suggested that he meet the Fifth Patriarch of Chan.

Huineng reached Huangmei thirty days later, and expressed to the Fifth Patriarch his specific request of attaining Buddhahood. Since Huineng came from Guangdong and was physically distinctive from the local Northern Chinese, the Fifth Patriarch Hongren questioned his origin as a “barbarian from the south,” and doubted his ability to attain enlightenment. Huineng impressed Hongren with a clear understanding of the ubiquitous Buddha nature in everyone, and convinced Hongren to let him stay. The first chapter of the Ming canon version of the Platform Sutra describes the introduction of Huineng to Hongren.

Hongren also explained to Huineng that the Dharma was transmitted from mind to mind, whereas the robe was passed down physically from one patriarch to the next. Hongren instructed the Sixth Patriarch to leave the monastery before he could be harmed. “You can stop at Huai and then hide yourself at Hui.” Hongren showed Huineng the route to leave the monastery, and rowed Huineng across the river to assist his escape. Huineng immediately responded with a clear understanding of Hongren’s purpose in doing so, and demonstrated that he could ferry to “the other shore” with the Dharma that had been transmitted to him.

The Sixth Patriarch reached the Tayu Mountains within two months, and realized that hundreds of men were following him, attempting to rob him of the robe and bowl. However, the robe and bowl could not be moved by Huiming, who then asked for the transmission of Dharma from Huineng. Huineng helped him reach enlightenment and continued on his journey.

Huineng’s teachings

The Southern School is associated with the teaching that enlightenment is sudden, while the Northern School is associated with the teaching that enlightenment is gradual.

This is a polemical exaggeration, since both schools were derived from the same tradition, and the so-called Southern School incorporated many teachings of the more influential Northern School. Eventually both schools died out, but the influence of Shenhui was so immense that all later Chan schools traced their origin to Huineng, and “sudden enlightenment” became a standard doctrine of Chan.

According to tradition, Huineng taught “no-thought”, the “pure and unattached mind” which “comes and goes freely and functions fluently without any hindrance”.

It does not mean that one does not think at all, but is “a highly attentive yet unentangled way of being an open, non-conceptual state of mind that allows one to experience reality directly, as it truly is.”

Historical impact of Huineng

According to modern historiography, Huineng was a marginal and obscure historical figure. Modern scholarship has questioned his hagiography, with some researchers speculating that this story was created around the middle of the 8th century, beginning in 731 by Shenhui, who supposedly was a successor to Huineng, to win influence at the Imperial Court. He claimed Huineng to be the successor to Hongren, instead of the then publicly recognized successor Shenxiu.

An epitaph of Huineng, inscribed by the established poet Wang Wei also reveals inconsistencies with Shenhui’s account of Huineng. The epitaph “does not attack Northern Chan, and adds new information on a monk, Yinzong (627-713), who is said to have tonsured Huineng.” Wang Wei was a poet and a government official, whereas Shenhui was a propagandist who preached to the crowd, which again leads to questions about his credibility.

“As far as can be determined from surviving evidence, Shenhui possessed little or no reliable information on Huineng except that he was a disciple of Hongren, lived in Shaozhou, and was regarded by some Chan followers as a teacher of only regional importance.” It seems that Shenhui invented the figure of Huineng for himself to become the “true heir of the single line of transmission from the Buddha in the Southern lineage,” and this appears to be the only way he could have done so.

Huineng’s most famous poem

The body is the bodhi tree. 菩提本无树。

The mind is like a bright mirror’s stand. 明镜亦非台 。

At all times we must strive to polish it. 本来无一物。

Must not let dust collect. 何处惹尘埃。

You might be interested in Great Tang Records on the Western Regions written by Xuanzang.